January 8, 2011

It took straight white people being shot in Tucson before folks begin to say it’s gone too far.

For nearly everybody else, endemic hate behavior in Arizona has been a basic fact of life and death.

When I lived in Tucson and worked on the Tohono O’Odham Nation, I worked in government- and NGO-run underground safe houses for hate crimes survivors. For the exceedingly painful and eye-opening year that I lived there, too many friends and fellow humans around me were beaten, shot, murdered, maimed, threatened, harassed and tormented – from the Tohono O’odham Nation to the end of my block, to the driveway of the house I shared with my girlfriend, to our own front porch.

How many is too many? The moment when there were so many that I lost count. When the beds at the shelter were empty because the person was in a grave.

While people hiked peacefully amidst the cactus, enjoyed a sunset round of golf, or taught sociology at the university, we had to tell people in hiding that there was nothing we could do to protect them in our state – all we could offer was what we called Greyhound Therapy: a one-way bus ticket out of town. Arizona had such few protections for them, their best hope was to leave. And the ones that didn’t get out in time didn’t always survive.

Many seem shocked by events in Tucson perhaps because this newest hate crime reveals a side of human existence that rarely makes it onto the front page, in part because the people in communities targeted by these crimes are rarely brought into the conversation. Indeed, the conversations that need to happen have no forum in our society.

We need to be bringing into the public forum those people whose communities have fought against hate for years, and probably have the ideas about how to change it. Instead, we have a long line of privileged people and faux-naive handwringing: “oh this is so shocking! it’s unthinkable! it’s unimaginable! it’s unspeakable!” while many of the rest of us know these acts on an intimate and personal level, and have often experienced it in some degree ourselves.

Yet in the honest, candid presence of those who have borne the brunt of America’s collective social failures, people become uncomfortable, defensive, protective…people take refuge and comfort in the familiar comforts of ignorance and fear.

We need instead to step up and make a compassionate connection to what’s difficult, and we do that by listening more to what disenfranchised people have to say.

When the sheriff said Tucson is the Tombstone of America, he mean Tucson is a graveyard, and he should know.

I suspect he meant it’s where the values of America go to die.

He also meant it’s where a lot of flesh and blood human bodies have been buried as a result of violent bigotry. A lot. A lot.

Homicidal violence and sociopathic hate are part of human nature, and exist in all corners of the earth since, presumably, the dawn of time. But some corners have laws and lawmakers who create protections for hate. Who enfranchise and protect the perpetrators, and who allow vigilante violence to careen unchecked through their communities.

Tucson is one such place. When people in power eviscerate or ignore the human rights of particular people, it creates a class of people who are considered disposable.

People often ask, “how can people conduct such violence against their fellow humans?” the answer is often, “because they don’t consider them human.” In Tucson, safe houses were the last refuge. And when the beds were needed by someone else, it meant that whoever went back out on the street often died.

Laws in Arizona protect these killers and bigots, and allow them to act – openly, with impunity and without consequence – against Latinos, Jews, blacks, gay people…

Now, there are consequences – but in the other direction. Against the lawmakers themselves.

Is this the moment when we – the National We, the Human We – begin to have these painful conversations? When we stop taking refuge in our own fear of discomfort? Where we learn how to listen to the communities of human beings who nobody’s wanted to hear?

I hope so.Because there’s been a lot of us going at it alone for a long time, with no help and nobody giving much of a fuck how many more were going to die.I hope that the outcome of this day is safety and civil rights for all the people who aren’t deemed worthy of life in Arizona, and everywhere.

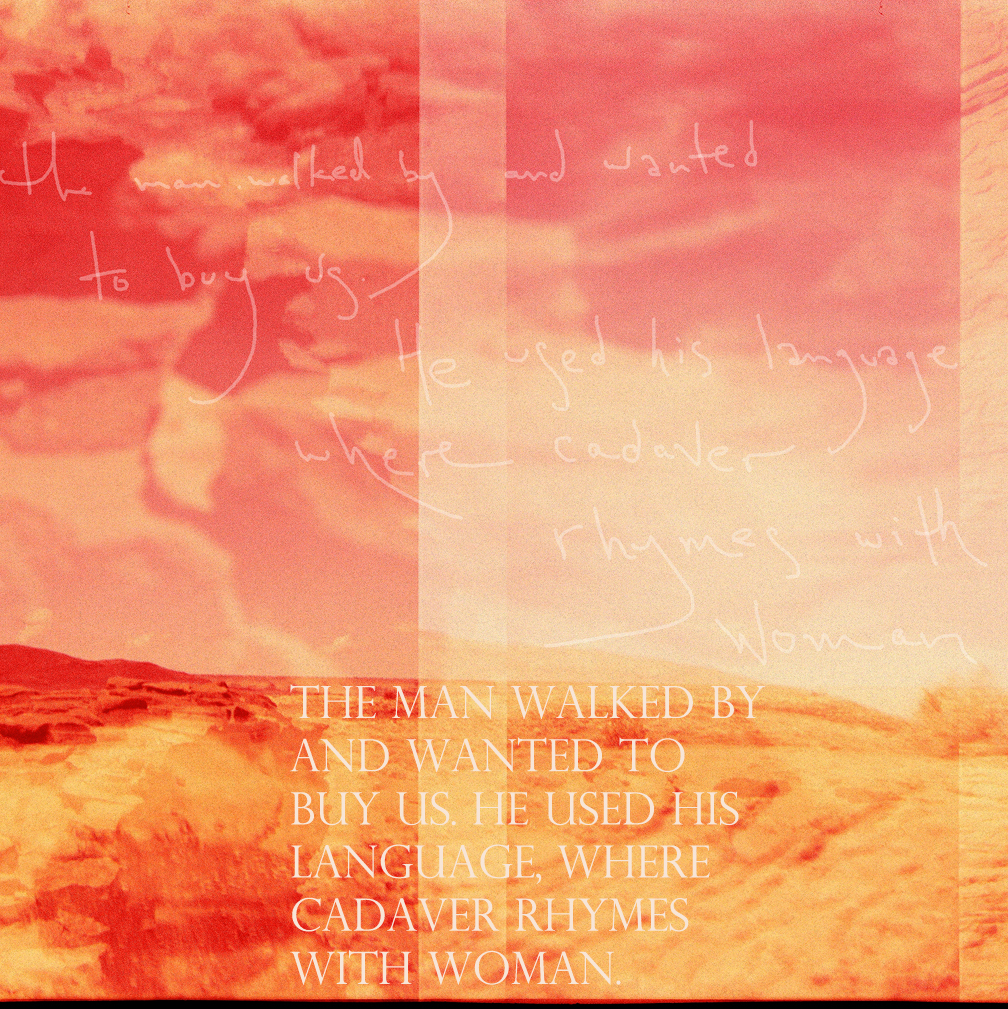

where cadaver rhymes with woman

Word. I was particularly taken with this statement: “When people in power eviscerate or ignore the human rights of particular people, it creates a class of people who are considered disposable.” That’s such a clear articulation of a truth I have been circling lately. Thank you, from Tucson!