December 15, 2010

This is part three in my Drunken Boat blog series exploring the resonance of absence and omission in literary and visual art.

PART ONE: http://www.drunkenboat.com/?p=1188

PART TWO: http://www.drunkenboat.com/?m=201011&paged=3

For the native tongue, a second language requires a tongue touching new teeth. A reshuffling of the shutter, where the scene is the same but the frame has changed.

Imagine two travelers from Taipei who have arrived in Munich for a conference on industrial magnets. After long days touring factories, the two women break free of their translator and embark upon an afternoon hike through the Bavarian countryside.

A late May rain descends and they gather beneath a black umbrella, and with their eyes cast down to avoid mud and puddles, they pause and admire a delicate forest stream more damp yet than wet, lined in rocks mossed and flocked with green. They hesitate and commune a while with the ancient holy purple hue of violets sprung up in lush velvet clumps.

They’re not much for cameras, but this is too lovely.

The frame contains, the shutter snaps: meaning is defined. It is a glorious spring morning on this one spot on the earth, wedged between factory and airplane – a brief moment where for once translation isn’t needed because green is green, and a flower is a flower, and a forest stream is always a forest stream.

I was there behind them, and we all kept walking, following the narrow shoe-worn path alongside the little flowered rivulet.

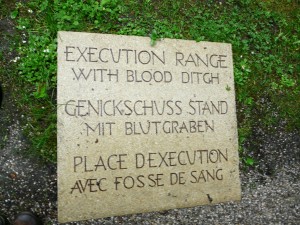

Within moments, the rivulet ended and we came upon a sign.

The women, who did not read or speak English, German, or French took a photograph of the sign (as, clearly, did I) before reaching in their jacket pockets to remove a small translation dictionary.

As they pieced together a meaning in four languages, their shoulders sagged, one of the women gasped, her body caving inwards as the camera dangled heavily from its wrist strap as though it was a dislocated bone. They clung to the umbrella handle as if it was suspended from the sky and could support their weight.

Without the sign, the blood ditch, the fosse de sang, the blutgraben would have seemed any other violet-lined forest stream in southern Germany.

Suddenly, the peaceful stream became a Nazi-dug trench to wick away the creeks of Jewish blood. And the picturesque violets? Drawn to the iron from the blood that drenched the soil, so much that it remained a source of fertility a full sixty-five years later.

That morning, I could hear the sound of text and image working in concert to shatter a reality, to show a truth that would otherwise be obscured.

This awkward, unfamiliar space of clumsy linguistic cross-conversation allows relationships to form outside of the typical channels of exchange.

Sudden intimacies take place.

Doors and windows snap open to mystery.

This is what Bertoldt Brecht – who lived and worked nearby this Nazi-built Blutgraben and fled their Genickschuss – demanded in his manifestos of episches Theater or “epic theatre”: that the audience must be disrupted. The image must be bracketed by text. Text must be accompanied by image. Movement by sound. All of it must jolt and jostle, all of it must serve to interrupt, must make us face something, must engender a shift from spectator to observer, must force the audience to re-examine an already-shattered picture of the world.

According to Brecht, “Gesamtkunstwerk” or “integrated work of art” can be a muddle. Yet it can also serve to stimulate the brain to a point of deep recalibration. As his Martinique comrade-in-art Aimé Césaire writes, “Beware of assuming the sterile attitude of a spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of miseries is not a proscenium, a man screaming is not a dancing bear.”

Considering Antonin Artaud’s Théâtre de la Cruauté (“theatre of cruelty,”) and considering Brecht’s “epic theatre,” – this is a theory of text, image and translation: disrupting stagnation through creating tangibly empty space in which the missing has space to expand.

“I would rediscover the secret of great communications and great combustions,” says Cesaire’s poem.

Indeed.