April 16, 2010

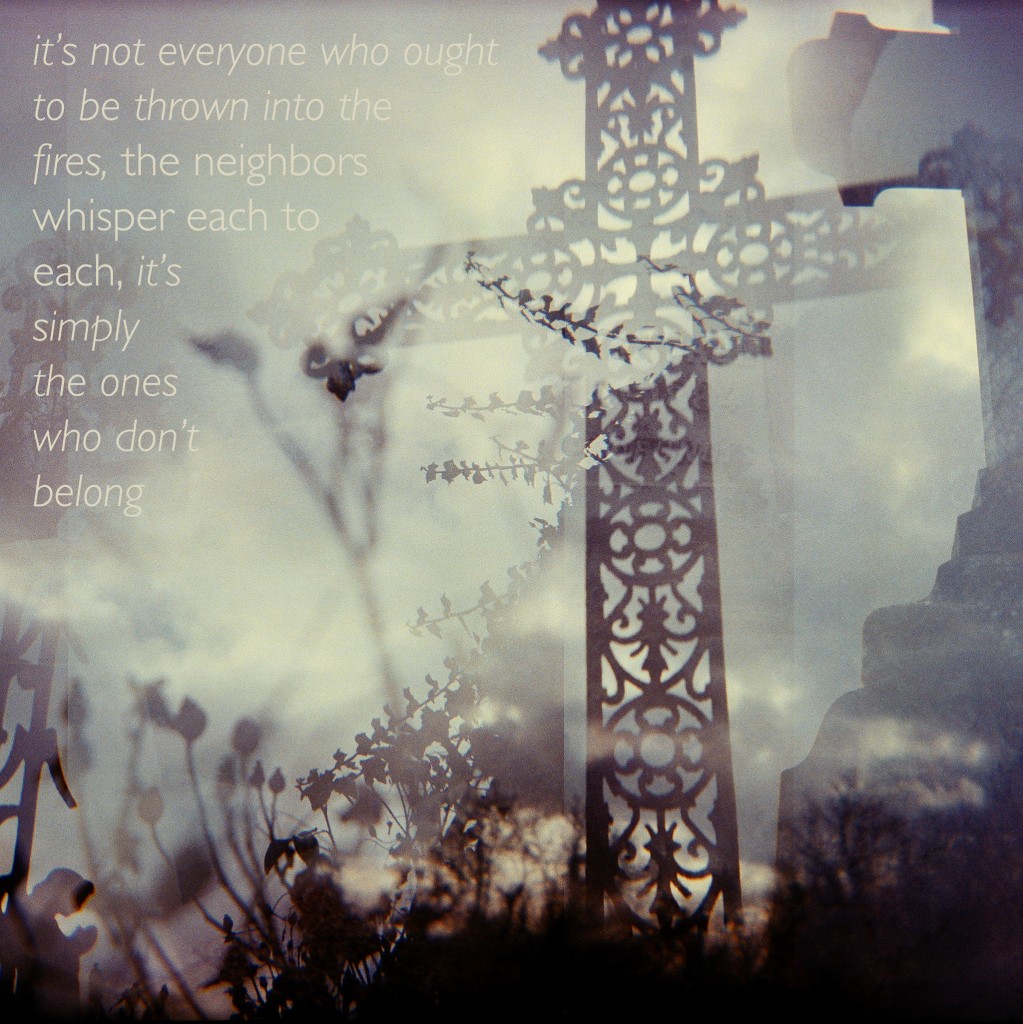

detail from FOSSOYEUR/GRAVEDIGGER (c) quintan ana wikswo

I must again mention Andrew Joron’s splendid Cry At Zero: “Pulling apart the lips of a white page reveals a curious network of fine bones, like those of an abstract bird…” (Fate Map, p. 21.)

As though reading is an archeological exploration of anatomy, an intimate violation, an intrepid excursion into a private civilization – or a revelation of mystery – a kind of cognitive alchemy, or an encounter with a biological conspiracy – some byzantine network of gravity-defying ideas, the way the hollow bones of birds seem filled with helium, their flight is so improbable.

There is something shattering about finding a dead bird, and also about finishing a good book. Both happened today, or almost did.

I thought I saw a dead bird in the yard this morning, but it was a peculiar configuration of extruded styrofoam clotted with tar and pine mulch. In Los Angeles, trash is more bird-like than the birds, who are understandably elusive. (If Los Angeles were a white page, it would indeed be covered with a network of bones. Almost all above ground, at least for now. A new city, as cities go, with most of its inhabitants not yet entombed. We worry these days about earthquakes, and count the amount of concrete above us.)

As for the self-indulgent grief at finishing a good book – there are worse bittersweets. I go through a separation anxiety when the last page is turned, and fast from words for a while. The new ones pile up until I am ready to love again.

One of the joys of being literate is the ability to curate a nice stack of reading, and plunge into the collisions and collusions between works. I’ve never been one for reading just one book at a time. I have to wait until there’s a stack taller than I am, and then topple it over upon myself and read my way out. In the excavation, they seem to coalesce with a satisfying synchronicity. As though my brain is a meeting ground for them, a reconnoitre point where they find friends and enemies, lovers and colleagues, and go at it happily until all the pages alloted them are consumed.

Afterwards, I try to group these books together that way on my shelves, in these excavated villages, as communities. If I grieve after the reading of a good stack of books, then perhaps I inter them together for their afterlife. I think about these books the way I believed, as a child, that animals spoke to each other in English whenever I wasn’t around. I used to hide around the corner from my dog, listening for hours. I want the spirits incarnate in paper to mingle, and birth new words, new worlds. I linger out of view of the bookshelves, pencil in hand, waiting to take notes.

I’m sad to have finished my beloved Christopher Isherwood’s The Berlin Stories, which documents the noose tightening around the artists and intellectuals in that city during the early 1930s. It juxtaposed itself against this irritating yet haunting Der Spiegel article – something of a paean to the American dream of its artists and intelligentsia – which offers a gloomy perspective on the zealous bigots organizing a media-savvy lynch mob-cum-political party in the United States in the early 2010s.

The message of the two pieces suggest that purges are problematic.

Everyone wants to destroy something.

I’ve just finished books about the Strasbourg witch trials, then the Strasbourg black plague Pogroms, and then another Der Spiegel article about last month’s death of Martin Sandberger, the SS officer who murdered the Jews of Strasbourg. These cycles of purge, of eliminating the visionaries, or at least the ones who don’t “belong.” It takes a critical mass (perhaps on all sides, though).

When I was surviving St. Petersburg last summer, a Russian joked to me that were it not for the whole crimes against humanity thing, the Gulag would have been a wonderful place to live, for it contained every last one of the most agile and creative minds in all the Soviet lands: all the most innovative artists, all the intellectuals, the pagans, the loose screws, the genius entrepreneurs of arts and letters, the avant-garde who would otherwise have propelled society into a new evolution. An exile, an exodus, an eden. Except, of course, my acquaintance murmured, everybody was murdered.

It is in this in-between-reading mood that I worked on a new poem sequence called FOSSOYEUR/GRAVEDIGGER, about the ghastly-but-lovely village where I stayed in remote eastern France this winter, in the house on the ancient Celtic burial mound. These rings of little villages had each known pyres for their witch trials. I eyed each woodpile with a nostalgic horror.

Here is one of the pictures I made in their cemetery with my old broken fascist camera. I spent nearly all my time in the cemetery, sitting with the local dead, who seemed almost relieved to have been excused from the whole deeply exhausting enterprise of living. The cemetery was a small walled place – maybe only 20 meters square. The bodies were stacked upon each other, perhaps equally deep. Twenty meters cubed, then, was the cemetery.

A few days before I left, I was poking around the cemetery in the neighboring village when I discovered quite a few human bones, green with mildew. A little surprised, a little chagrined, as though they had taken a wrong turn by following an outdated map, or had foolishly left the house without an umbrella and were taking shelter in the shadow of a tombstone, wondering quite what should be done next.

It was another of many startlingly endearing moments within a desecration, where everything is simplified to vulnerability and ineptitude and ignorant innocent, and somehow it just renders down to serve as deeply human. I sat with the actually quite gorgeous, stately, sculptural bones as comfortably as though I were at a bakery counter, chatting with a beautiful woman about a craving for brioche. And then I took their snapshot – at times I’m inappropriately, hopelessly American.

In that town, most of the other citizens are underground, a curious network of fine bones, like those of an abstract bird…