January 7, 2015

click here to purchase a copy of this issue. Or check it out online.

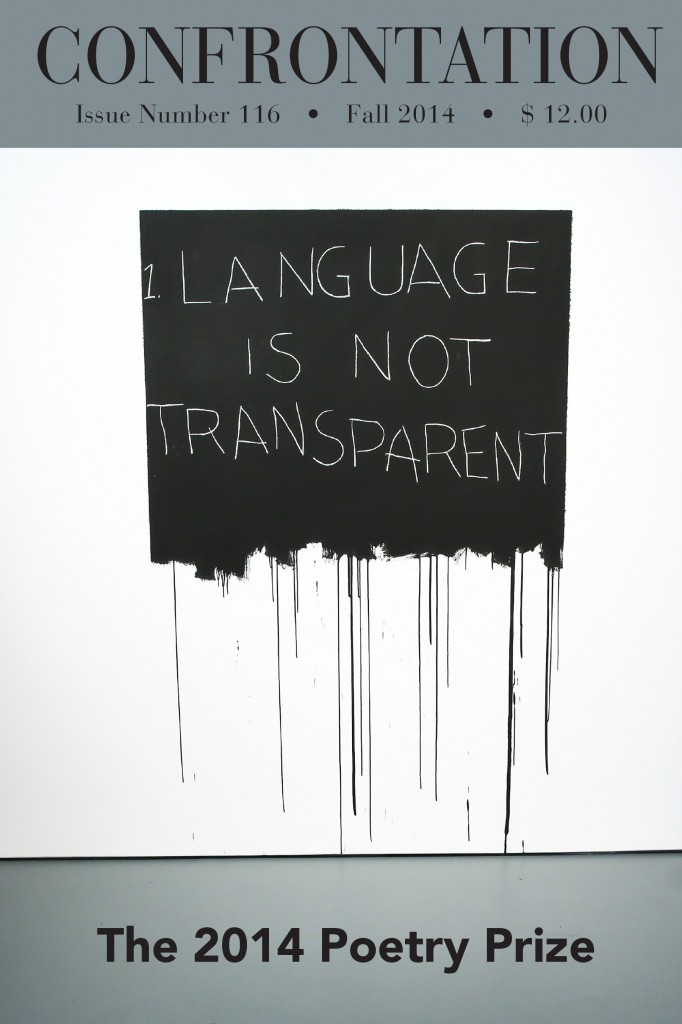

I have what is apparently a very confrontational new essay in the new issue of Confrontation. At its core, the essay considers whether the bigotry of an artist and his or her milieu is peripheral to his or her work. Within that framework, I write about the Mel Bochner retrospective at the Jewish Museum and how it illuminates the sociocultural legacies and implications of the 1970s white male minimalist conceptualists, the priorities of the art market, and the antidote that I see forming in the contemporary art practices of the Yam Collective and their withdrawal from the Whitney Biennale, the No Wave Performance Task Force and its protests of the Carl Andre retrospective at DIA Chelsea, Micol Hibron’s staggeringly comprehensive (en)Gendered (in)Equity poster campaign, and others.

In her foreword, Confrontation editor Jonna Semeiks calls the article “a clever, spirited, and forceful review,” and lodges a strongly-felt complaint against it: “We have to strive to keep prejudice and all other peripheral things out of our assessment. We have to give the artist his donnée; and who an artist’s friends are, whether he and his friends and the art establishment itself are hostile towards or dismissive of the work done by female artists, whether they are indeed misogynistic, whether art has been “corrupted” by commerce, whether the art “business” really is just a business, like any other, interested only in the bottom line. whether galleries and museums merely play follow-the-leader rather than use their considerable resources to seek out what is best: all of these things, I would argue, are peripheral to the work of a particular artist and ought to have no place in our assessment of it.”

Prejudice and bigotry (which, incidentally, includes misogyny) is certainly not peripheral to anything, nor are core questions surrounding artistic and institutional ethics within the field. An individual artist has no inherent right to be absolved from having her or his work considered along their stated ideology, and the broader ideologies of their milieu. Leni Riefenstahl, James Balwin, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and hundreds of thousands of other artists are routinely examined within the context of their ideologies and ethical positions concerning core aspects of the culture to which they are contributing and in which they are participating.

An excerpt from my response:

“From the Carl Andre retrospective at DIA:Chelsea (a show that tidily sanitizes his involvement in the death of artist Ana Mendieta) to the various Mel Bochner shows doing the rounds, a waning generation of highly saleable but yawningly outdated artists are enjoying a last spasm of investment muscle from the one-percenter art world…a world dying yet smiling from within the chokehold of hedge fund managers with billion dollar art storage crypts.

The minimalist-conceptualists have achieved a strong historical legacy and renown for their public and private cruelty towards female, African-American, Asian, and Latina interlopers in their field. These methods of exclusion remain an active topic of conversation in the fields of visual art, civil rights, and museum curatorial practice. Throughout recent months, anger is increasing around the entrenched bigotry and civil rights injustices in the fine art marketplace. There have been a series of protests by Christen Clifford and the No Wave Performance Task Force held outside DIA:Chelsea calling attention to the institution’s erasure of Carl Andre’s misogyny, his involvement in the artist Ana Mendieta’s death, and the role of the other (white, male) conceptualist minimalists who sold work to bankroll his legal defense and the character assassination of Mendieta, a young Cuban female feminist artist. This Spring, a trenchant and incisive protest was waged in national media by the Yams Collective around the 2014 Whitney Biennale’s near-complete exclusion of women and people of color. In Los Angeles, Micol Hibron’s staggeringly comprehensive (en)Gendered (in)Equity poster campaigns publicize the gender balance (or imbalance) in all of the top contemporary art galleries in Los Angeles.

As many have tirelessly pointed out, it’s also just plain boring art. A homogeneous, derivative duplication of the dominant paradigm. Bring those kids some Twinkies – it’s time for the moon landing. And make sure the maid gets home on time – this suburb has twilight laws for blacks.

These very contemporary present-day protests of antiquated aesthetics are an attempt to bring at the very least an honesty to the drug-front bodega of the art world. Because just like the drug front bodega, the art world bodega thinks that even though they’re charging ten dollars for that fifty cent box of crackers, you have to shop with them because there’s no place else to go.

I hope for an art world in which time is our friend, and not an enemy who forces us to continually revisit the inadequate, innervated artwork of antediluvian bigots whose price for attaining such behemoth status is their loss of nimble, agile, relevant creativity.

There are still quite a few luminous, incisive artists whom the machinery has not yet anesthetized to the point of unconsciousness, atrophy, and irrelevance.

When the thick glass doors of the Bochner show closed behind me, I returned to my studio and feasted my mind on a thriving, verdant hedgerow of text-and-painting artists – Carrie Mae Weems, Glenn Ligon, Sophie Calle, Mark Bradford, Barbara Kruger, Robert Colescott, Jean-Michel Basquiat, William Pope.L, Kara Walker, Renee Green, Jenny Holzer, Lorna Simpson. Like Bochner, these are conceptualist artists working in text and painting, but unlike Bochner, the work they’re creating has not passed its expiry date.”