June 22, 2010

This summer I am a resident artist in the very tiny village called Schwandorf [full town name added after my departure]…well, let’s just say “somewhere in Bavaria” and we can clarify it after I leave. My proposal was to come and work on a collection of poetry and photographs – they accepted, and I arrived. In a sense, I am following Helen Thomas’ advice to Jewish people: go home to Germany.

Ok, let’s see how that goes. Why not try it for three months? It’s a pretty village. There is a church, a beer garden, an iron works, and a cluster of old houses amidst fields, forests, and rivers. Several hundred people live here. My studio is in a little modern glass-and-steel structure on the banks of the river. There is a second church, and a cemetery, and a butcher’s, a baker’s, a gas station, a grocery store, several intimate beer gardens, and of course in such a small and remote village, the train station is a very important focus for the community.

Each morning I wake up and wonder how to arrange my day. I took a week in Italy, and returned on the night train through Germany. This weekend, I decided to overcome my innate and purportedly outdated phobia of pogroms and take a leisurely stroll through the Bavarian countryside. Instead, I encountered freshly spraypainted swastikas, SS runes, and NPD – the neo-Nazi far-right political party. Since then, new ones appear here and there.

The Kunstlerhaus is located directly adjacent to an ironworks where Jews (and other prisoners of the nearby Flossenberg concentration camp) were enslaved. In a walk around the block, I discovered a street named after one of the original founders of the Nazi party, owners of the ironworks, and convicted war criminal. It’s horrific to call that street my home.

A trip to the beauty parlor by a fellow (Jewish) artist yielded a list of restaurants, bars and clubs where we should not go because of the number of recent beatings by neo-Nazis.

For the past few days since that walk, I’ve felt more comfortable staying inside my glass-and-steel studio.

Some mornings, I wake up and wonder whether I should just get away from my studio and the local swastikas, and spend more time exploring the neighboring villages. A day trip! Anywhere within 150 miles is close enough to get there and back in one day.

Here is a map that shows roughly 150 miles in every direction from where I am.

Each blue pins marks the location of a concentration camp. I gave up after about 100 pins. There are a whole lot more. The nearby camp of Flossenburg had more than 100 major sub-camps. But there are other camps that had more subcamps, so probably if I were to truly complete this map, one would see only blue.

Let’s say each blue pin marks the unmarked graves of several hundred thousand murder victims.

So day trips are beginning to seem less desirable to me. The few that I’ve undertaken have the same history: at best, a little brass plaque tucked away on the side of a building that states that Jewish human beings once were alive, and then were sado-scientifically tortured over a long period of time before being sado-scientifically murdered.

Maybe the plaque gives names. Maybe it gives numbers. Maybe it gives details about the sadism.

Or maybe there’s no little plaque at all, just a lot of happy summer people drinking beer and eating ice cream and paying their telephone bills.

How about instead of going 150 miles away, I just go 150 meters?

Well, if you go 150 meters to the north, you see this example of the SS runes. Just like at the plantations in South Carolina, this region is famous for the beauty of its trees and flowers.

Aren’t they beautiful? What a vivid and lovely color of green. Just to the left of the swastika on the other side of the building, there is some sort of very nice purple flower.

It’s just a little difficult to concentrate on the beer and the natural beauty, because I’m a little preoccupied, wondering if any of the people here who are spraypainting this town and saying the only good Jew is a dead Jew would really apply that to me.

Here is another place about 150 meters from my studio. It’s in the woods. It’s not marked. Perhaps there are lovely purple flowers growing there, too.

Since being in Bavaria this summer, I have noticed that a particular kind of low-lying flower seems to grow in areas of mass graves and executions. I think it thrives on all the iron in the soil that comes from the blood of hundreds of people.

![A mass grave of murdered Concentration Camp prisoners in the Schwandorf forest. Date: Apr 1, 1945 Locale: Schwandorf, [Bavaria] Germany Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Irving Heymont Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum](https://bumblemoth.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/425931.jpg)

A mass grave of murdered Concentration Camp prisoners in the Schwandorf woods near the train station. Date: Apr 1, 1945 Locale: Schwandorf, Bavaria. Germany. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Irving Heymont Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The question, really, is whether someone who wants to harm a Jew will walk past me, recognize that I am a Jew, and decide to harm me.

Like the hairdresser said, there are regular beatings of anyone who seems to come “from outside.”

I have lots of time to think about that here. For instance, while I’m walking to the grocery store.

The only route to the grocery story is a small lane that passes between the river and a low concrete wall, past the German Soldiers Memorial. There are yellow swastikas painted along the wall. A few days later, there are green swastikas, too.

Each person who passes me on the path makes me tense: what is going to happen now.

After the grocery store, I go stand at the train station debating whether or not to leave town. It occurs to me that other Jews of the ages of my parents and grandparents once stood here, wondering whether or not to leave town.

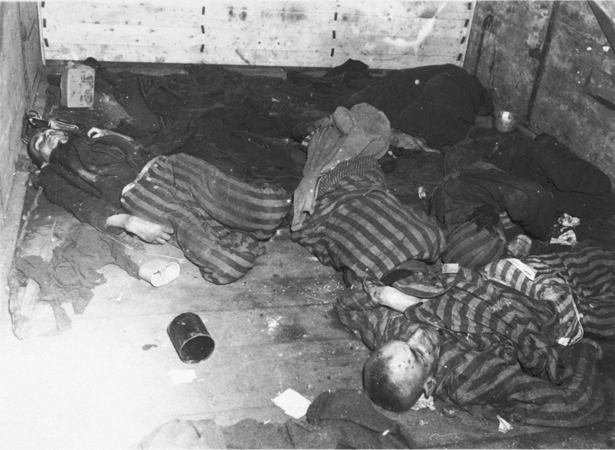

I found this photograph of some of them. They are some of the last Jews to pass through the Schwan… train station.

Now there’s just me.

The bodies of former concentration camp prisoners lie in a railcar in Schwandorf Date: Apr 1, 1945 Locale: Schwandorf, Bavaria, Bavaria. Germany Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Irving Heymont Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The other week, I was talking to a local historian, and I asked her whether this little village ever had any prisoners from the nearby camps pass through. She said, “No, there was no camp in this town.”

I said, “I know, but did the prisoners ever pass through here? I am trying to visit the graves and pay my respects.”

She replied, “During the war, a lot of people pass through,” and then turned and walked away.

I hadn’t brought with me the photographs of the local villagers unloading bodies from the train cars. She would likely recognize her parents, her aunts and uncles, her neighbors…names now cast in bronze on the Nazi Soldier Memorial a few feet away. It’s always been a small town.

It would have been more difficult for her to recognize the faces of the local Jews in the photographs, because they are mostly only skulls.

There are communities in Germany with heavy stewardship duties: residents are custodians of some very ugly places. When towns fail to prevent the mistakes of the past from reappearing, they not only fail me – and all the future me’s – but they fail all those who were murdered, too. This is similar to how I feel about sites of former plantations in the United States, like Bleak Hall Plantation on Edisto Island.

The graffiti is absolutely unacceptable. Not just it being painted, but the fact that it is not removed. Why isn’t it removed? The few people who have talked to me about their disinterest in removing it, say that it doesn’t affect them, so they don’t really notice it.

What happens when you put up swastikas and SS runes in towns where those you want to destroy have already been destroyed?

Where they aren’t taken down because they don’t apply to anyone still living?

Do they want them to serve as a warning? Perhaps they also mean, if this applies to you – get out.

Throughout my entire life, I have sat beside survivors and listened to them telling the part of their story about Leaving. When To Leave. Whether to Leave. How to Leave. Why to Leave. An entire legacy about leaving Germany.

Only survivors get to talk about leaving Germany – only the ones still around to tell me about it.

The ones who didn’t leave Germany, didn’t survive.

I don’t want to be here anymore. But I don’t want to be driven out, either. I feel like one of us should be here, just to stand and say: YOU DID NOT SUCCEED.

But since I am standing here completely alone, I might as easily say: YOU BARELY FAILED.

Regardless, it’s lonely.

It’s not just a physical isolation that comes when everybody else like you has been murdered and you’re the only one stupid enough to return to the scene of the crime.

It’s also an emotional and psychological and spiritual isolation. It’s not like much of anyone – here or anywhere else – really wants to spend time around this subject matter . That extends to me, the bearer of this subject matter. The bringer-upper of painful conversations. The one that, soft-spoken, respectful, still clears out a tour group and gets left standing alone in the room.

The one with the funeral wreath, wandering around Bavaria with no one place to set it down.

I had come to pay my respects, and most of the time there’s not even anywhere to go lay a stone, or stand and think. There is nowhere to mourn except everywhere. I could just turn in circles, reciting the Kaddish, hoping that it lands in the right heap of rubble…

Perhaps for the rest of the summer, I try to learn the name of that little flower that drinks the iron from the blood of murdered Jews.

Or maybe I ask around for the whereabouts of the bluebottle flies, who eat decomposing human bodies. I suspect the Bavarian bluebottle fly now contains enough Jewish DNA to qualify as a part of my community.

I keep my eyes out for the flowers and the flies, and wherever I find them, there we are.