April 6, 2010

from the War Birds series (c) Quintan Ana Wikswo

Pigeons can recognize themselves in mirrors. Humans think we can as well, but it’s possible that we recognize what we look like, but not who we are.

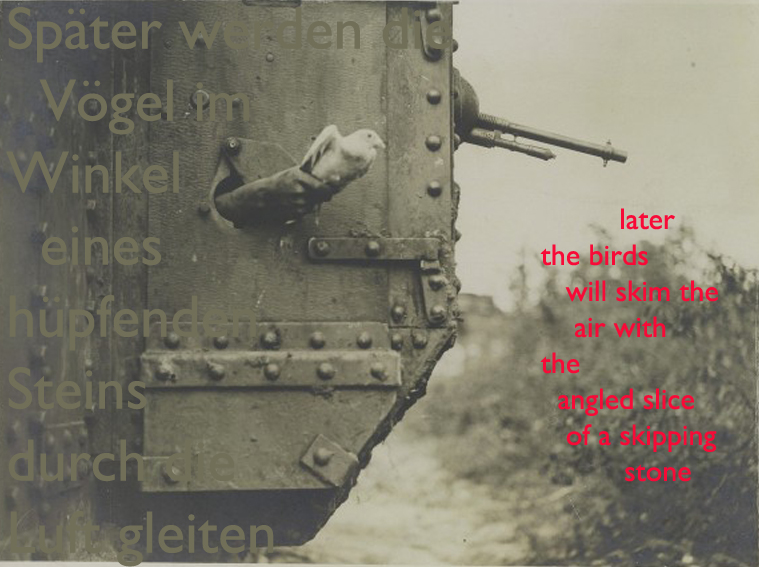

This battlefield photograph from the National Archive of the Netherlands documents a British soldier releasing a carrier pigeon from a tank on the Western Front in France. The birds flew back and forth carrying messages between men in tanks and men on foot in the infantry, rather like the dove of peace communicating from Noah’s ark, except this time the ark is armored, the earth is awash in human blood not water, and there is no olive branch yet to be found.

A few months ago, I spent time wandering along the Western Front in Vosges, France. The villages were often dilapidated and minimally inhabited. Cemeteries were filled, then covered with a layer of dirt and filled again. Cast iron sculptures of empty helmeted rifles in every churchyard.

The town in which I grew up in the South was still reeling from the American Civil War and slavery-era crimes against humanity – a quiet bone-bred grief that comes from living on blood-soaked soil. Perhaps its the iron that creates a magnetic pull towards sorrow, the inchoate kind that becomes as familiar as your own skin. We showed visitors the bullet holes in many of the walls of older buildings, and the strange lines formed by earthworks, and black stains on hardwood floors in houses used as battlefield hospitals. Go to Carnton now, and they have covered the stains with persian rugs. Before the pop-up mansions and mini-malls, a tin can of minnie balls and shrapnel commonplace in sheds and basements.

I remember being taught to place my finger in a bullet hole, and see how deep it went. As I got older, I thought the bullet holes became more shallow. It was only my finger growing longer.

But I learned how to feel the way the wood was crisp as charcoal where the bullet had burned it, to retrieve a little soot under my fingernail, and resent the knife marks that had eventually dislodged the ball, the gouges smoothed by the fingers of Southern children, each learning how to feel the wall of a house for wounds, each marveling as our fingers lengthened and grew too large to fit. Confederate flags and Klan pilgrims. Leg shackles rusting in piles in the root cellars of abandoned plantation houses.

Eastern France felt similar. Prominent in every village square’s churchyard was a freshly painted memorial to the dead of the First World War. Flowers would appear at regular intervals, nearly one hundred years later. Memories do not fade, they just move deeper inward. The only memorial I saw to the dead of the second World War was at the Gare de L’Est station in Paris, under a staircase near the tracks where French Jews were sent to extermination camps.

The majority of the broken and semi-demolished cameras I use in my printmaking and photography are battlefield cameras from WWII. They are the survivors. They have eyes, and their memories are recorded on strips of film, and then harvested. They were built to take knocks. I feel as though I’m taking them on pilgrimages, back to the scene of the work for which they were manufactured. The battlefields that I photograph are covered with flowers and grasses, parking lots and daycares. But the cameras seem to recognize the other landscape that lies within, even with new rolls of film wound through. Where is the camera that took this photograph of the human hand outstretched? A hand, so vulnerable it needs to be encased in iron and steel, and so dangerous despite its apparent vulnerability.

This is the most recent of the War Birds series from my Orphan’s Mourner body of work. Others include No.1and No.2. The text is drawn from a story from my collection in progress (my gratitude to Dorothea Herreiner for her work translating some of that collection into German).